The AI boom: a reality check

Why the revolution is unlikely to come as fast as politicians hope

AI’s advances continue to astound, but how sure are we that it will inspire an economic revolution? The idea of a future redefined by AI has become such a cliche that it’s tempting to switch off entirely from a debate characterised by sci-fi-style hyperbole. It’s hard to distil, from this, any serious attempt to quantify the dynamics of a credible upside. The OBR has just published its review of the (sensible) literature which is the basis of my latest column for The Times. There

The AI-upside scenario is repeated so often - as if it’s an inevitability - that the expectation is shaping our lives now:-

Stock market valuations are based on the assumption that AI revolution is real. If it’s not, then we’re in the biggest bubble in history.

Sixth-formers are making university choices based on bets as to what AI may do to graduate jobs. Companies worried about AI are already cutting back on grad jobs.

Politicians who see reports of an AI revolution starting in just a few years are tempted to borrow heavily now, in the belief that they’ll soon be bailed out. Reeves has huge tax rises scheduled for 2029, by which time Trump’s White House thinks tech gains will have doubled American GDP growth.

Millions are working in companies planning for AI-enabled transformation, even though AI is in its infancy and far from reliable. Mathias Döpfner, ceo of Axel-Springer, earlier this year said he intends to double the company’s value in five years by becoming the “leading provider of AI-empowered media in the free world.”

But not all tech revolutions mutate into economic uplifts. The iPhone and Netflix era transformed how we work and communicate, but didn’t stop us sinking into economic morass. Tools of mass distraction and homeworking trap may have created more productivity problems than solutions.

AI’s advocates say it could transform societies, start a tax revenue avalanche and “make work optional” as Elon Musk said recently in Saudi Arabia. Politicians are easily seduced by the idea of a horn of plenty. We’ve heard this before: nuclear power would make ultra-cheap energy; computers would transform what children learn at school. Tech revolutions that are plausible in theory often fail to pan out in real life. The cycle we have to bear in mind is not so much tech, but our recurring propensity to believe that a revolution is just around the corner.

The OBR has performed a reality check, to quantify the chances of this happening and scale the upside. It’s consensus nowhere near what the tech-optimists say, but strikingly better than pessimists fear.

Bulls and bears on the AI spectrum

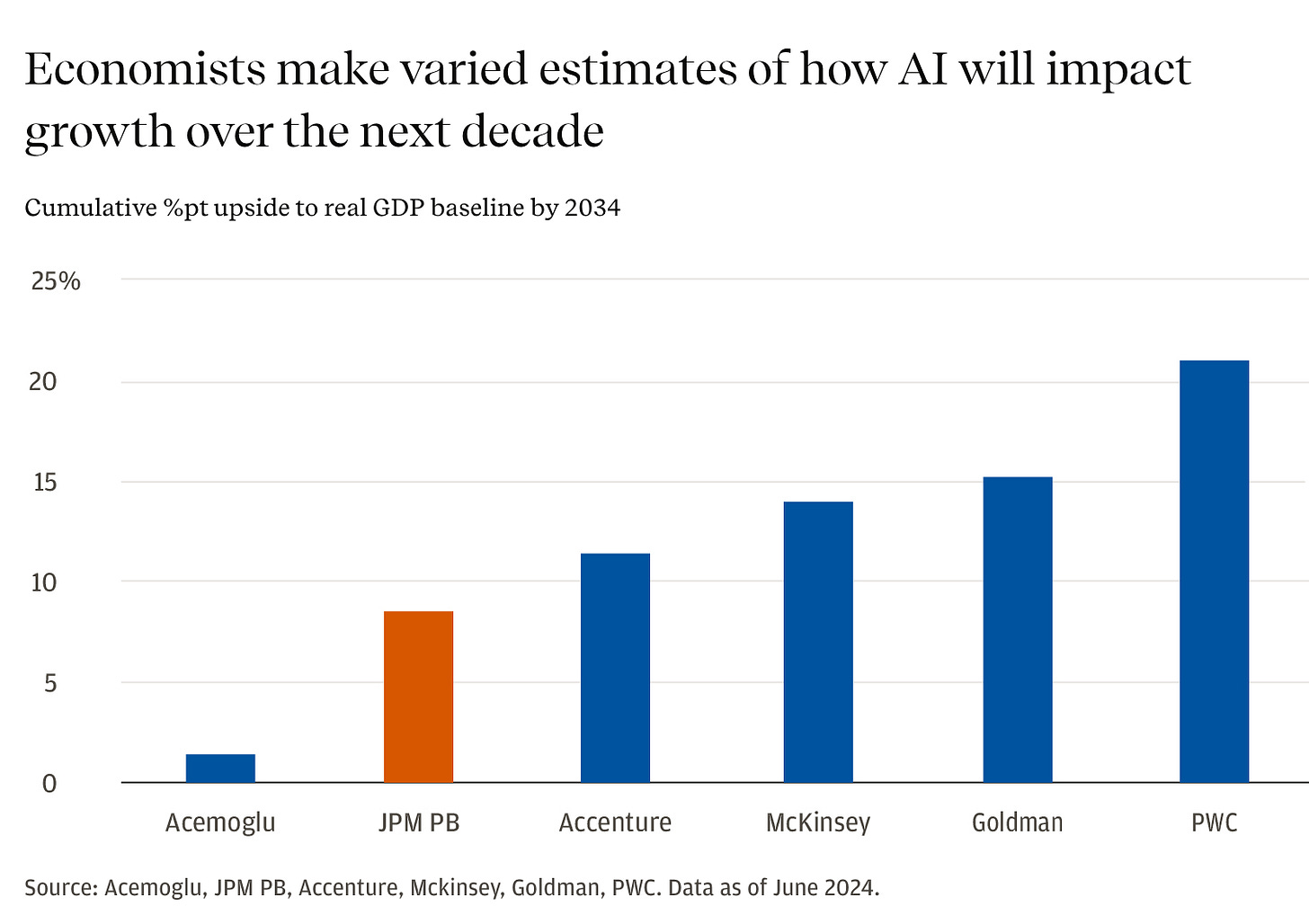

Let’s start with MIT’s Daron Acemoglu, author of Why Nations Fail. He thinks its hype and has published a framework for gauging its impact: he thinks just 5pc of jobs can be automated, he thinks. He makes GDP forecasts accordingly. JP Morgan last year published a chart on the range of AI forecasts for 2035 (that is: how much AI will have expanded the US economy by). Acemoglu is at the bottom. At the other extreme lies a PWC forecast made in 2017, years before ChatGBT. The OBR isn’t on the below chart, but its assumptions would put it a bit higher than Acemoglu.

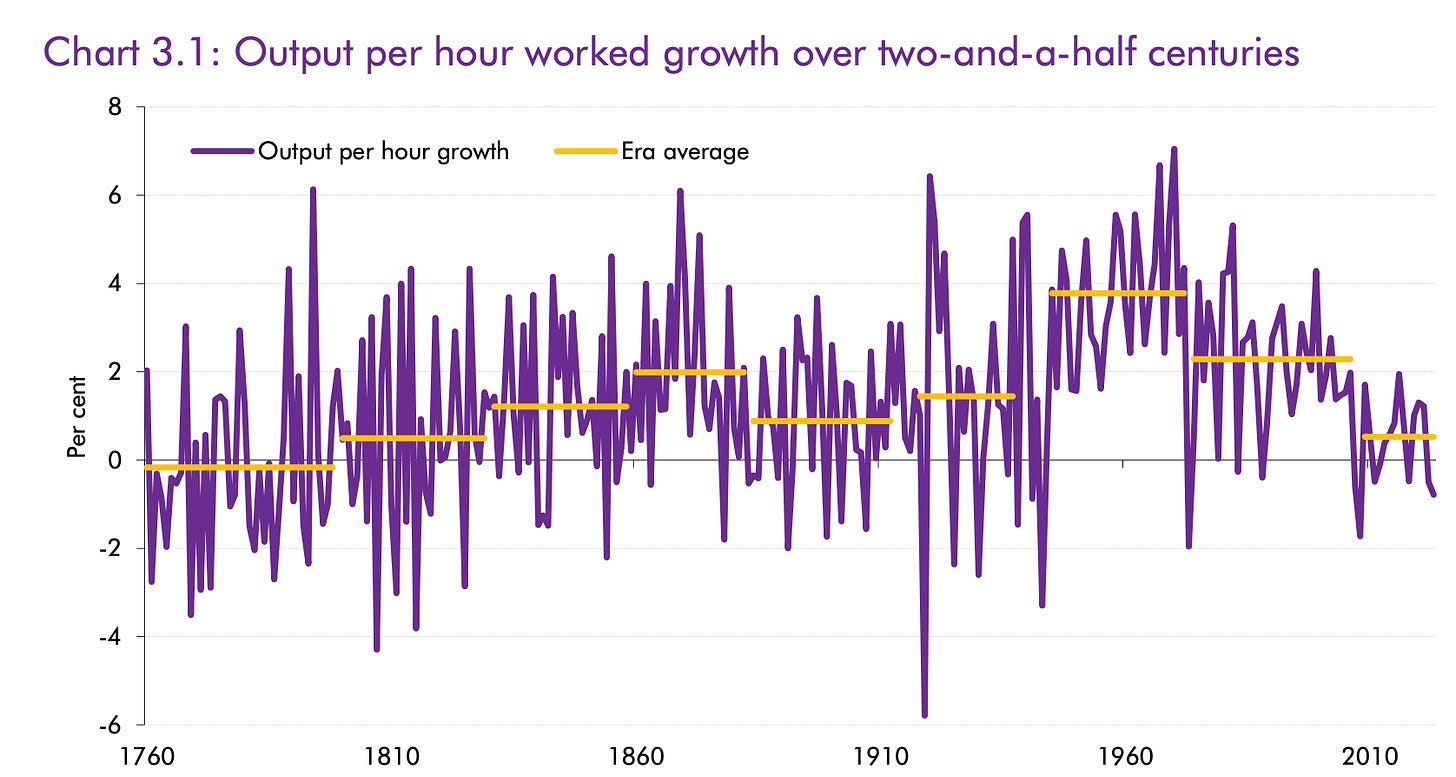

A brief history of tech revolutions

The OBR starts by dividing the last few centuries into eras. Industrial Revolution: productivity growth ~2pc. Postwar UK experienced its ‘golden age’ of productivity by using US industrial techniques so ~4pc growth. The computer age arrives, then online and globalisation. But after the 2008 crash the UK hits its worst-ever fall in productivity growth. This is the funk which all Western democracies are trying to escape. It took a while for the OBR to believe we’re in a low-growth ‘era’ (as opposed to a freak post-crash or post-Covid dip) so the below diagnosis is new.

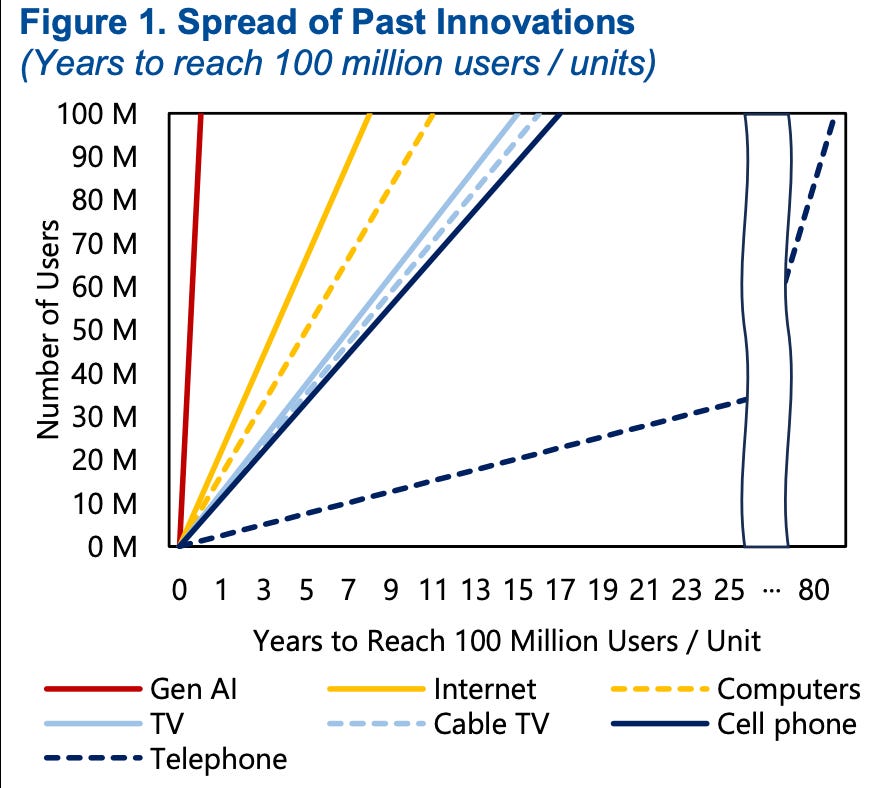

Prosperity is usually driven by new technology: transport, first globalisation wave (late 1860s) internal combustion engine (inter-war period), laptops etc. But old technology revolutions took decades as they needed miles of wire for electricity, telephones, etc to expand. Generative AI will do it far more quickly because we all have these devices at home and in our pockets and upgrades take seconds. “It took 15 years for the personal computer to increase the economy’s productivity,” says JP Morgan. “AI could do it in seven.” A 2025 IMF study illusrates the trend..

Examples of an AI revolution….

Banks Say a bank employs 500 call centre staff handling 10,000 calls per day. Each agent handles about 20 calls in an 8-hour shift, spending time looking up account details, navigating multiple systems and writing notes afterwards. An AI assistant listens to calls in real-time, automatically pulls up relevant account information, suggests responses, and drafts the call summary. Each agent now handles 35 calls per shift, not 20. The bank can either handle 17,500 calls daily with the same staff, or handle 10,000 calls with 285 staff.

Timber! I met a young Swedish entrepreneur a few weeks ago who has invented AI technology that scans logs, works out where best cut and gets between 0.5pc and 1.5pc more wood from each tree.

Building A quantity surveyor spends two weeks producing a cost estimate for a new building. They manually measure drawings, look up material prices from various suppliers, calculate labour requirements based on experience, and build a spreadsheet. AI uploads drawings, extracts measurements, pulls current material prices from supplier databases, generates a first-draft estimate in hours. The surveyor spends three days checking the output, adjusting for site-specific factors. A two-week job becomes a four-day job.

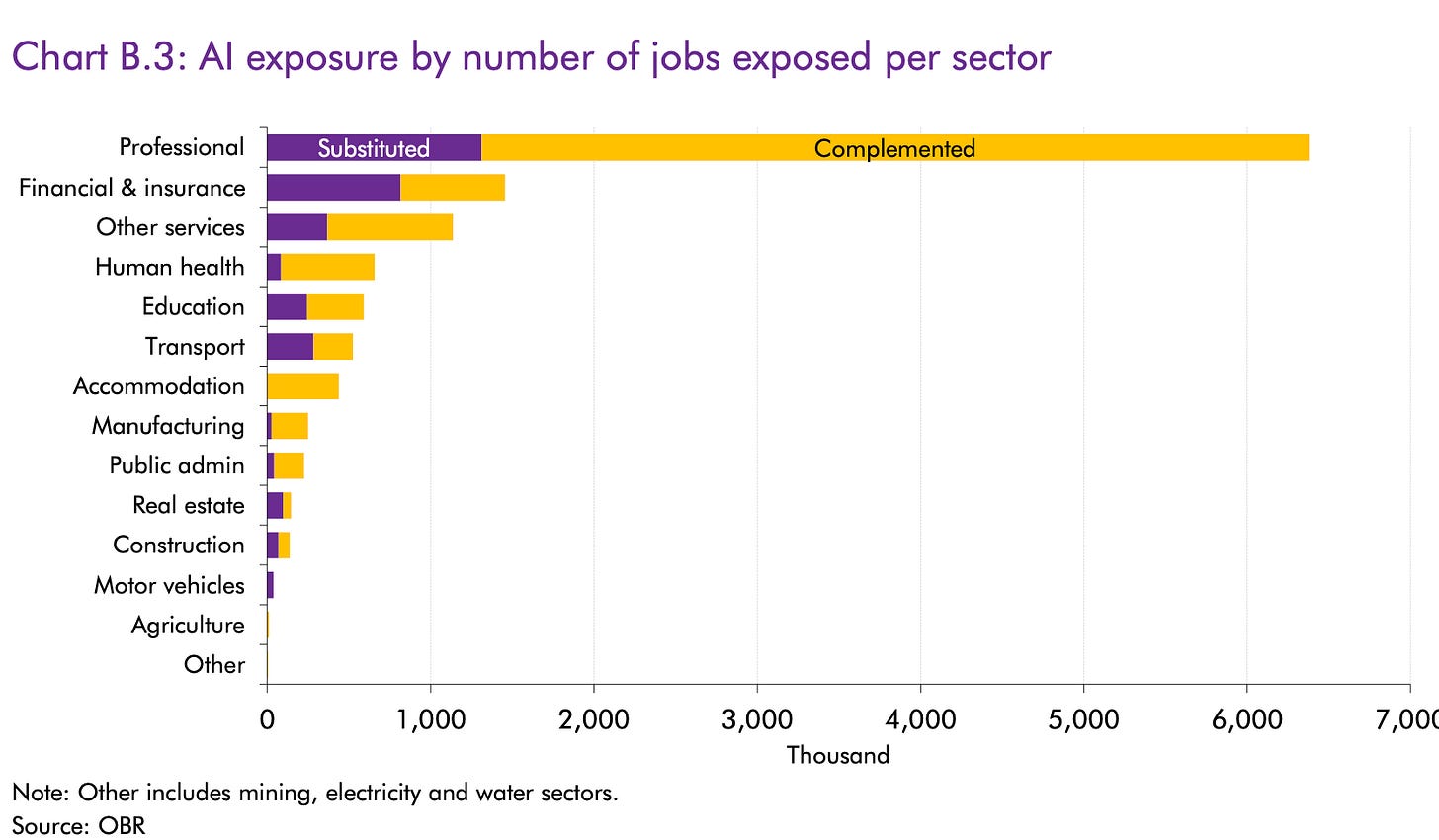

So to get a feeling for AI’s impact on an economy, you need to work out: what kind of jobs, what kind of impact? It’s a big exercise, and one the OBR has formally modelled. The UK is the first country to have this attempted by a governmental institution.

Still looking for a man in finance?

In the study, the OBR does what it does best: identifies the most robust studies, finds consensus estimates and shwos its working. It has built its own model using America’s O*NET job definition system, adapted to UK occupations. It reckons ~40pc of UK jobs are “exposed” to AI over the next decade (at the higher end of the 5pc to 70pc range). It finds most exposed jobs will be complemented (workers become more productive) rather than substituted (replaced). And in which sectors? Bankers: look away now.

The OBR thinks about a million jobs in finance will go, and you can hear these fears everywhere. My son Alex is 17 and I was driving a friend of his home the other day; the son of a hot-shot financier. I asked if he’s planning to follow his dad into the industry. No, he replied, his dad isn’t sure there’ll be many opportunities in that industry left by the time AI is finished. The boy is now going to read Ancient History and uni and position himself in a job - as yet undefined - safe from the ‘clankers’ (a derogatory the young are now using for AI). Whether this is right or wrong, my point is that the prospect of AI transformation is great enough, and the potential risk for graduate jobs seen to be big enough, as to be shaping decisions right now.

For comparison, here’s Goldman Sachs on which American jobs are most at risk from AI-automation.

If 44pc of legal jobs can be switched, I can assume these lawyers are using AI that’s not as prone to hallucinating (concocting stuff) as the LLMs I use (ChatGBT, Grok, Claude, Perplexity). I would not rely on a single of of them for a single task.

The OBR report is going on the assumption that..

40pc of UK occupations are exposed to AI

33pc of AI-exposed tasks will be feasibly be automated within a decade…

…and those tasks will cost 32% less

This adds up to 57% UK labour share of GDP

So the OBR’s big conclusion…

“Based on these inputs, we derive our central scenario which suggests AI could boost the level of economy-wide productivity by 2.3 per cent over the next decade.”

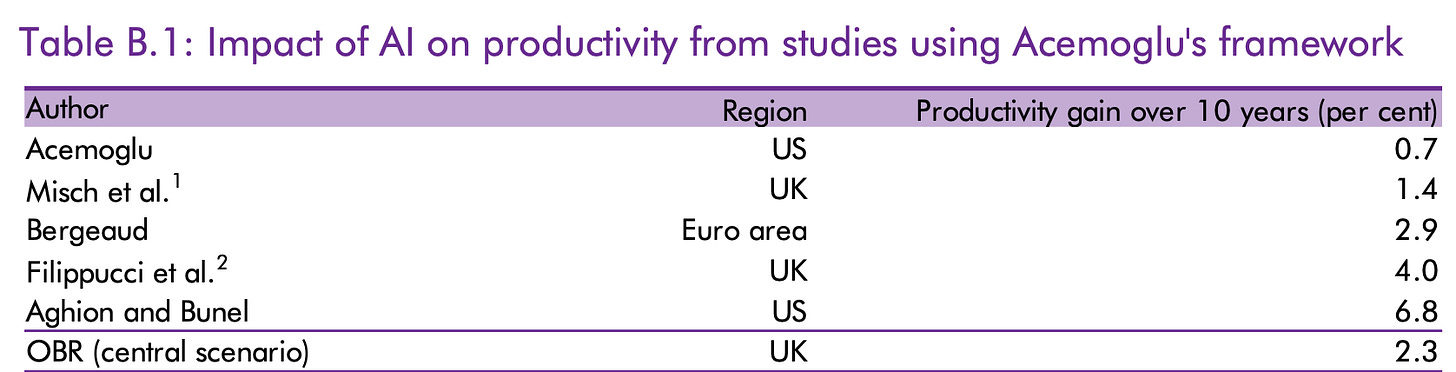

Why the differences? The Acemoglu framework

It was Acemoglu whose model decided not to treat AI as a general-purpose revolution, and breaks down the economy into specific tasks and asks which AI can realistically perform. His conclusion: just 4.6pc of jobs. He thinks AI will boost total factor productivity by a cumulative 0.7pc over the next decade - nowhere near the transformative claims made by tech optimists.

The OBR has taken the Acemoglu task-by-task framework but plugged in its own assumptions to come out with its a more optimistic 2.3pc figure. It provides a list of others who have taken the Acemoglu task-by-task approach and places its 2.3pc midway through that range.

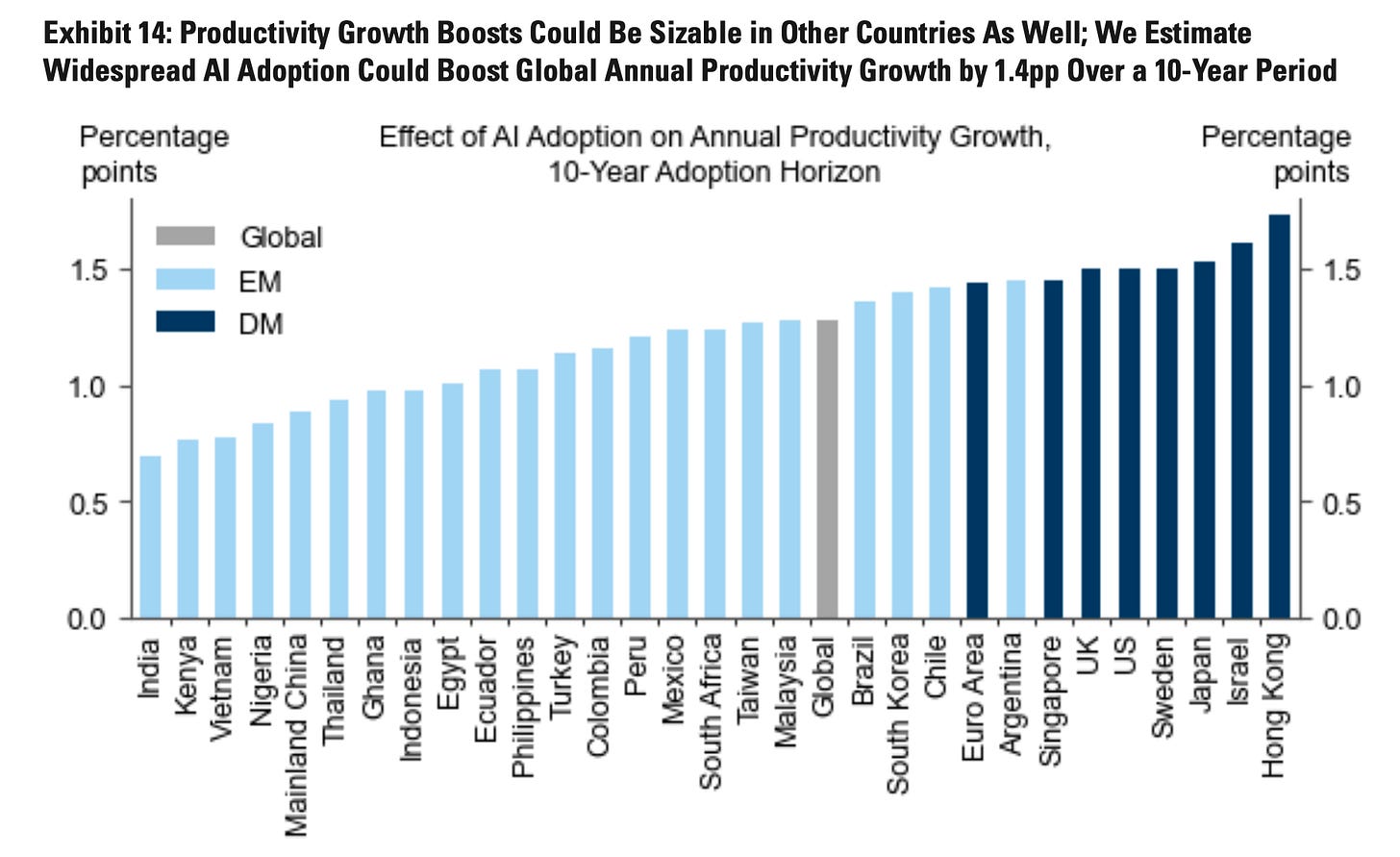

Why are Goldman Sachs figures more optimistic?

The landmark Goldman Sachs study (Briggs and Kodnani, Mar23) talks about 1.5 percentage points of additional annual growth “during the decade following widespread adoption” — but crucially they don’t specify when that adoption happens. It’s a conditional, abstract forecast. The OBR is making an real-world forecast for 2025-2030, assuming slow uptake on a J-curve.

McKinsey (Chui et al, 2023) goes further estimating generative AI could boost productivity growth by 0.5 to 3.4 (!) points a year through to 2040. Their range is enormous because it depends entirely on adoption speed which, like Goldman, they say is “hard to predict.” Crucially, neither is forecasting super-growth now. They’re saying if AI gets widely adopted and follows historical patterns, then you’d see these gains. This is why the OBR is using the Acemoglu model: it wants to anchor this in reality, not an abstraction. And this explains the difference. One is real-world, the other is an fully-AI adaptive world. In Goldman’s scenario, the UK’s opportunity is as big as America’s (below).

The Mar23 Goldman Sachs report does give one real-world 2034 estimate: that AI lifts American GDP growth by 0.4 points. Which is quite bullish.

The OBR’s AI ‘transformative’ scenario

The OBR thinks that its realistic best-case is to end up with a productivity boost of 0.8pc annually. That would be more productivity growth than Britain has averaged since the financial crisis (0.5pc) so total productivity growth could hits 2 per cent - territory not seen since the early 2000s. But not exactly futuristic. The OBR’s verdict: these assumptions “are fairly unlikely” to materialise, and even if they did, most of this impact would come after 2035. But it’s notable that the OBR doesn’t rule it out. This 0.8pc is still a far cry from Goldman Sachs’ estimate of 1.5pp during peak adoption, and well within McKinsey’s 0.5-3.4pp range. The OBR is being conservative even in its most optimistic scenario.

And what it’s all just a flop?

The OBR also runs a “conservative” scenario where AI adoption remains limited—cost barriers persist, skills gaps don’t close, firms fail to reorganise workflows. In this world, AI’s productivity contribution is negligible (less than 0.1pp annually) and Britain stays stuck at 0.5pc productivity growth indefinitely. The OBR treats AI disappointment as a genuine possibility, not just a theoretical exercise. Its summary: “AI could potentially increase annual productivity growth by anywhere between 0.0 and 0.8 percentage points over the next decade.”

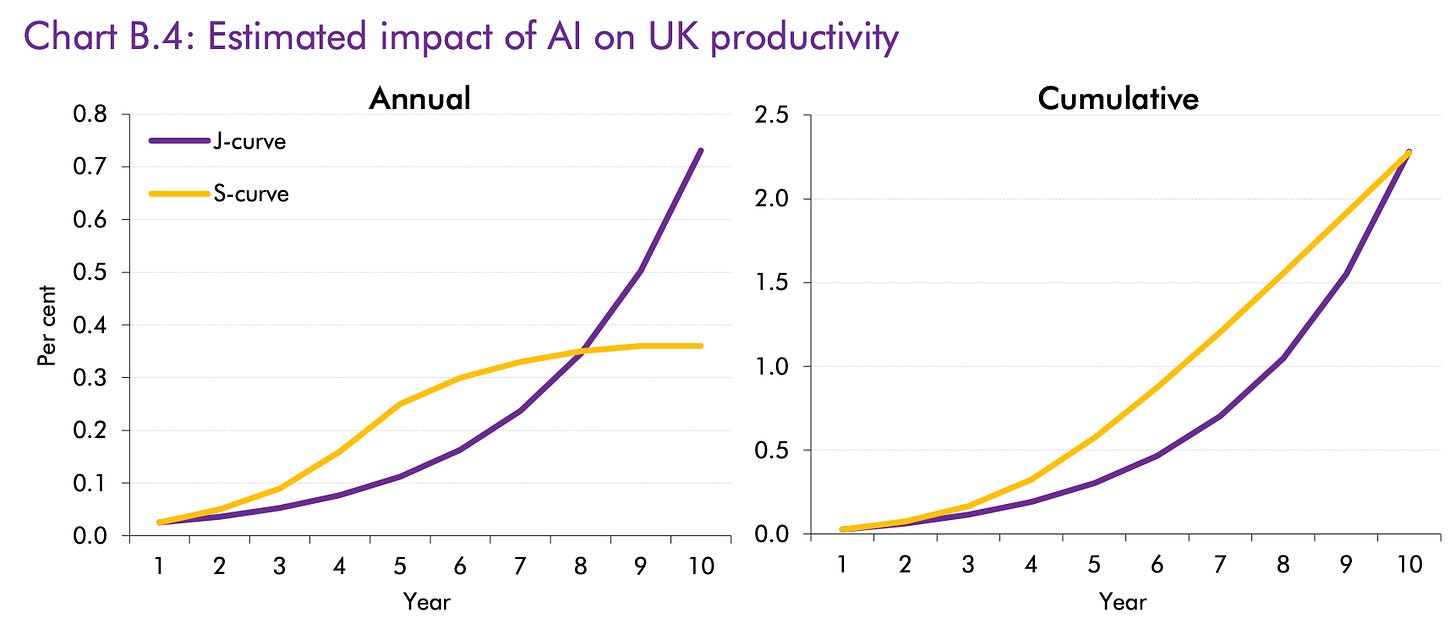

Usefully, the OBR graphs up scenarios for AI productivity lifts. That it strats slow and then takes off (the purple J-curve) or boosts - then settles (the yellow S-curve). The OBR gives both scenarios and a central estimate, somewhere in between the two. That’s 0.2pc by 2030 (or year five).

So the OBR has already given Reeves a (small) AI boost

The OBR admits that AI could well come faster and lift productivity forecasts to 0.5pc by 2030 taking it back to 1.5pc. This would lift projected growth, people’s assets and morale. But the gap between downside (0.5pc productivity growth) and upside (1.5pc) represents radically different fiscal futures. And 0.2pc with 0.6pc on sight is not exactly being mean. A recent Penn University study model saw AI’s boost to productivity growth “strongest in the early 2030s, with a peak annual contribution of 0.2 percentage points in 2032. After adoption saturates, growth reverts to trend.”

The hype and hysteria about AI makes it hard to work out what’s going on, or what’s being seriously modelled. But the OBR’s bottom-up methods seem more plausible to me than the scenario-based McKinsey and Goldman models. The PwC ‘seize the prize’ report, which had the most stunning models, came out in eight years ago. While tech has advanced faster than was then expected, the economic models seem to be sobering.

That’s not to say it won’t revolutionise certain sectors. The Spectator achieved a 5x increase in value over 2009-24 as tech helped us outpace and out-innovate larger, slower rivals. But that was not tech itself. It was a change in working practices, with multi-platform journalists and an ‘ask for forgiveness, not permission’ culture of innovation. We did it with amazing people, not amazing tech. Axel Springer could well double its value using AI but that will depend on the skill of its humans, not the speed of its kit.

My hunch is that those technological achievements - the Grok videos, the Claude programming - are unlikely to translate into real economic dislocation or transformation in the next five to eight years. The tech-optimist scenario is plausible, but right now hard to reconcile with any economic or assumption framework.

Expectation could create its own reality. The hope / fear of AI revolution will affect the size of gambles politicians take, the number of graduates firms hire - and how much stock markets are valued at. My sense is that, in all of these areas, the hype is significantly running ahead of the reality. A few more studies like the OBRs may help bring things back down to earth. As Acemoglu concludes: “economic theory and the available data justify a more modest, realistic outlook for AI.”

AI could well transform our economy - but not any time soon. And if it does happen, Starmer, Trump and Reeves are unlikely to be in office to reap the dividends.

Has the OBR considered the potential downside of its more optimistic scenarios? They appear to assume that AI will be complementary to existing work structure as opposed to (IMO) an environment in which workers are replaced. If there is mass dislocation of the workforce (or even selective dislocation) then what? UBI?

Some sound logic in this analysis Fraser, but many of the projections are in isolation of the ‘action and reaction’ effects that AI will influence but not necessarily cause….

I say ‘influence’ rather than cause - AI will inevitably be a causal strand running through all of our lives, but there may be many other ‘unknowns’ as yet that are likely to affect almost everything.

I’ve spent my career in tech - and in particular analytics - and seen bubbles, booms, fads and iterations of the same thing, all hyped by techies and marketers like myself, but never as much by politicians as we see happening this time.

They seem to have developed vastly more foresight than the rest of us all of a sudden! Without any evidence of being qualified to postulate so enthusiastically!

AI definitely will affect productivity. New jobs will appear; others will disappear. But if I were a politician or indeed an OBR analyst, I wouldn’t be as certain as they seem to be that this will be a panacea for all economic ills - and certainly ( as you seem to agree) not during their political tenure.

One certainty is that other stuff will happen - unforecasted events - that may have a bigger influence on outcomes for society than AI. We got a taste of it with Covid. We could see unfortunate events occurring even more frequently - as a result of AI.

I’m no Methuselah, but I’m happy to predict AI won’t be all plain sailing for the markets in general, or for humanity.