Why autocracies should not co-own newspapers

Is Keir Starmer about to sacrifice a vital pillar of press freedom?

Just over a year ago, Parliament passed a law declaring - on a point of principle - that autocracies should not own or co-own newspapers. The Bill, a backbench rebellion foisted upon the Tory government, showed the institutions of democracy protecting each other. Rishi Sunak, who was all set to keep the Emiratis sweet hoping for their investment, had to yield.

But the Emiratis did not sell. They defied Parliament and clung on, waiting to see if Keir Starmer’s government might be more biddable. They have had a strategy: to buy influence in democracies by ‘investing’ in wind farms, airports and other pieces of infrastructure. To buy influence, in effect, by ‘investing’ in politically-sensitive projects that no other normal investor would put money into. So they could play keep on berthing Xi’s ships and welcoming Putin as a hero - while being treated as an ally and investor by a cash-strapped UK government.

Shortly after their bid for The Spectator, December 2023, they gave Putin a 21-gun salute. Here’s the video:-

It now seems that their decision - to ignore Parliament and pressure Starmer - has paid off. The new law had a caveat: it didn’t want to stop (say) the Japanese teachers pension fund from investing in media. It left that bit blank. It seems Lisa Nandy, the Culture Secretary, has now widened this to allow 15 per cent for any foreign owner: including governments and Redbird IMI. Which, in spite of its protestations to the contrary, is a fund majority-owned by Sheikh Mansour, the deputy PM of the Emiratis.

How can Nandy justify this? I’m told she intends to use weasel words, saying her co-owner compromise will somehow unlock much-needed investment for newspapers. This is something I know a lot about, having spent the last year as Spectator editor involved in its sale. We kept our eye on industry profits. Have a look at this: the Telegraph is not in need of a cash injection. On the contrary, it’s making shedloads - it is being not just successful but industry-beating successful - under the most strained circumstances imaginable. So why is it making cuts, being ordered to scale back its US ambitions etc? Not because of any lack of subscribers for the incredible work its journalists are doing: the problems only come due to the ownership of Sheikh Mansour’s Redbird-IMI:-

Such profit margins are absurdly high for any company, let alone one in a fast-changing media environment where investment is vital. Again: The Telegraph is having to make cuts and hold back on obvious investment plans - not because it lacks revenue, but because it’s being bled.

When we saw Sheikh Mansour on the list of bidders for The Spectator (via his vehicle RedBird IMI ) we dismissed him straight away. The very reasons the Deputy Emirati PM wanted to buy the Telegraph and Spectator were the reasons they should not be allowed to: they’re a government, an autocracy, seeking leverage over a democracy.

Lloyds Bank was arranging our auction and was (in a way that RedBird is now not) mindful its role deciding the future of the free press. Lloyds behaved with honour, mindful of the sensitivities of a bank deciding the future of Britain’s free press. This sensitivity led it to delay the process: to my chagrin, as a quick sale could have spared us the agony being hawked like a rug in a souk. But there was sensitivity nonetheless. Lloyds, we knew, would never sell a newspaper to an autocracy: as a matter of honour.

Am I being naive? No: Pearson drew exactly the same line selling the FT. The Emiratis had offered £1 billion for the FT, a knock-out bid - or would have been had Pearson thought them a respectable bidder. But it took a lower (£844 million) offer from Nikkei of Japan: a private company in a democracy. The Emiratis could not find anyone willing to sell a newspaper to an autocracy. Especially one so cosy with Putin. So the Emiratis were snookered. Shut out of the auction. Lloyds would not select them for the Telegraph, just as Pearson rejected them for the FT. Lloyds aim was ‘best fit’ not ‘highest price’. But then came the Emirati coup: a brazen move which none of us predicted.

How the Emiratis won the titles

At any stage, the Barclays could end the auction and reclaim both titles if they somehow found the £1.2 billion. Repay the debt, reclaim the collateral: that’s the law. But who would give them that? Especially as the assets were, together, worth nothing like £1.2bn. Rough estimates put The Spectator and the Telegraph at about £500 million - and Very had complicated debt issues that made its value £300m at best (other reports put it at about zero). The idea of anyone paying £1.2 billion for assets worth £600 million to £900 million was seen as fantasy. It did not feature in our (extensive) scenario planning.

When the Emiratis did swoop, it made no financial sense. Until you worked out the real goal: they were paying far more than the assets were worth: but they would be the first autocracy, the first government, to own, or co-own, a newspaper. There are rules world over limiting how much autocracies can snap up: the idea is to get their cash, without giving them influence. That may work in a shareholder model where a 15% owner is outvoted. But in a newspaper, if you’re a co-owner - a co-proprietor - then you get the status. A chill is sent down the newsroom: best not go sniffing around stories about the Emiratis (or their allies). You’ll be seen as a troublemaker; bad for your career.

This chill factor is present in every newspaper. The proprietor may want his journalists to all be fearless, but word gets out about who the proprietor’s friends are. Journalists - who have appalling job-security - have an incentive to self-censor. This is why dodgy people are drawn to media ownership: for this co-proprietor status. Some of those on the Spectator’s bidder list were - quite literally - convicted criminals. Or, in my view, soon-to-be-convicted criminals: looking for power, authority, status. They paid the most: it was dirty money.

Of course, anyone owning or selling a media company will like the idea that Sheikh Rattleandroll is allowed to bid, as it massively ups the price and value. When I was considering my own MBO for The Spectator, one of the reasons I baulked was that the lenders (I’d have needed to to borrow about £50m) will want a decent return on an exit in five to seven years. The most lucrative exit (I found out) was to flog to take dirty money: a sheikh, a Chinese magnate with links to the CCP; an ‘investor’ with zero previous experience in media but with a hell of a reputation to launder. The quickest way to make money in media ownership is to do a ‘clean’ deal and then segue to a ‘dirty’ sale. What the autocrats lack is media owners who would actually sell: in a way that Pearson and Lloyds did not. I felt that if I did my MBO and the industry hit turbulence, a highly-leveraged buyer would face pressure to sell to a bad actor. The acquisitive autocracies are a new force in media ownership, throwing a golden lifeline to an industry facing falling sales. Remember: a company, or any asset, is only ever worth as much as someone else will pay. When Parliament banned newspapers from being sold to autocracies, it would have cut the market value of all papers - whether on the auction block or not. If every newspaper had shares quoted in the stock market, Lisa Nandy’s 15pc rule would have led to a jump in the value of those shares. This places a structural tension between the financial interests of media owners, and the principles of press freedom. That was why the law was needed.

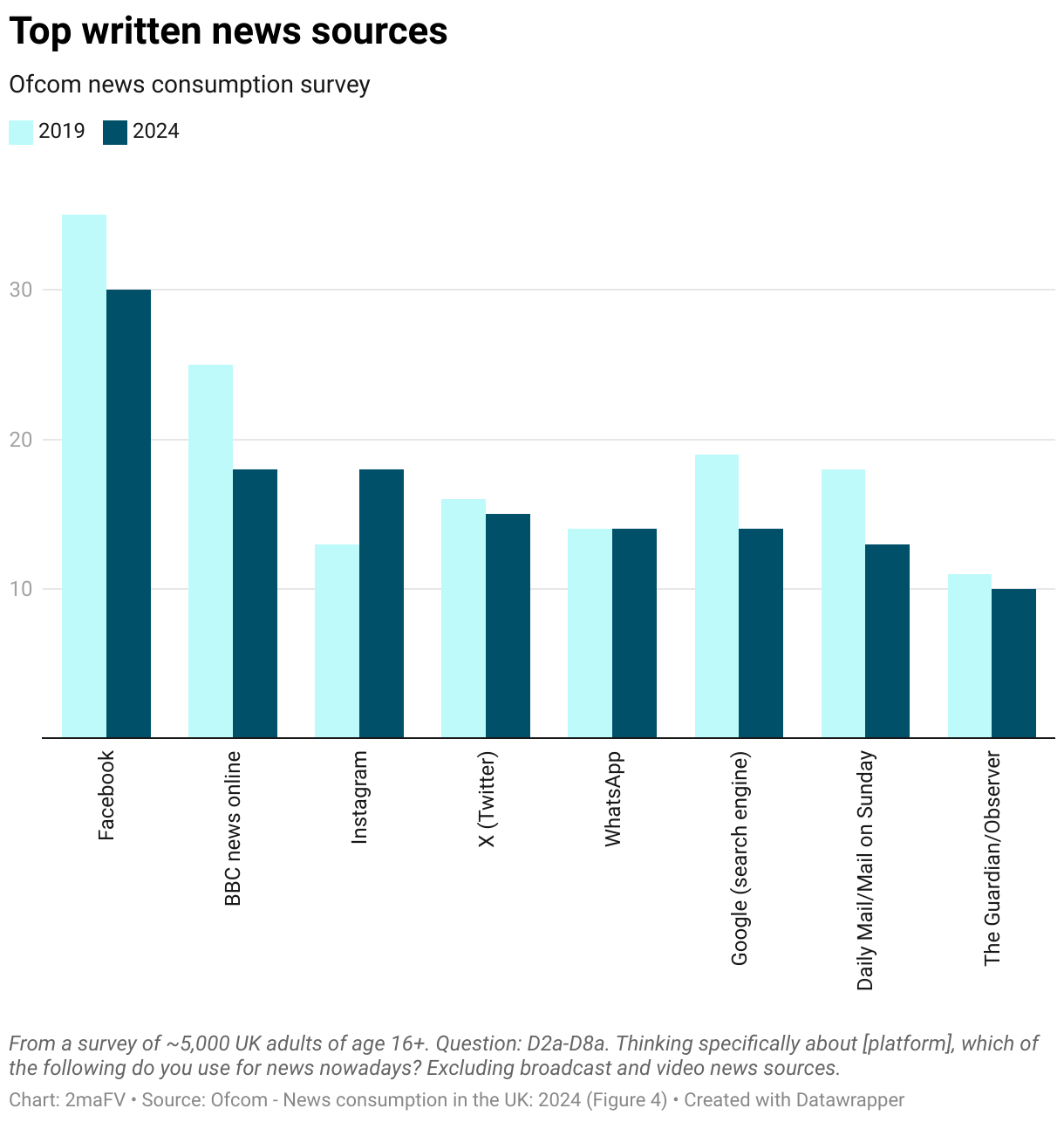

Lawmakers may soon come to regret this. How long will it be until they switch from fretting about an over-mighty press to a panic about the collapse of genuinely independent newspapers? More people now get their news from X or Instagram than from any newspaper and this should worry the government more than a caustic newspaper editorial. As Elon Musk recently demonstrated, his future is one where conspiracy theorists can run wild, in the hope that it will eventually lead to truth.

Graphs like the above explain why governments of Finland, France, Italy are actually subsidising newspapers. The UK does not need to do so: it can protect press freedom by stopping successful, profit-making newspapers from ending up being co-owned by the autocratic regimes they should be exposing.

So what happens now? Will the Emiratis now settle down as co-owners of the Telegraph - and can we expect far fewer Charles Moore columns on their antics? Or can Starmer salvage the principle of press freedom before the pass is sold? Even now, it’s not too late.

Free speech for people living here, for people with skin in the game. No guarantee of free speech for Russian bot farms or foreign pamphleteers.

Or football teams.

Or anything.